When you hear the words 'gender gap,' you probably just assume

that it's a gap where the women are below the men, like the wage gap (not

getting into that here). But the gender gap in education is multi-faceted in

that both boys and girls

are at a disadvantage in certain respects.

THE FEMALE DISADVANTAGE

Last week, I talked about how America is falling behind in math

education. This, of course, isn’t the only issue with math education. More

upsetting than our national issue is the worldwide problem; women fall behind

in math on a global scale. This issue was first introduced to the public sphere

in 1980, when Johns Hopkins researchers suggested that ‘superior male

mathematical ability’ was to blame for the gap.

Of course, this more than ruffled some feathers. And years of

research have found that women aren’t inherently bad at math. A few things

inhibit female success in mathematics, and all of those reasons are cultural.

The problem begins where it always does, in primary school. In

this stage of math education, the main goal is to master the basics with enough

skill to be able to apply them down the road. Doing so with aplomb requires a

certain amount of math confidence that girls are lacking.

| When you google 'elementary school teacher,' 97% of the pictures show a female teacher (image source). |

This lack of confidence isn’t born, but bred. Knowing “that young children are more likely to emulate adults of the same gender," that 87.16% of primary school teachers are women,

and that “elementary education majors have the highest rate of mathematics anxiety of any college major," it makes sense that girls would start to lose math confidence very early on.

If this self-doubt is imbued early on, it can follow girls all the

way up to secondary education and beyond. This means less women in mathematics,

which means less role models for girls, which means less women in mathematics,

and so on.

I believe that some ways to improve this aspect of the education

gap are to remove stereotyping from the elementary classroom and to encourage a

heavier emphasis on math literacy among education majors. What do you think?

Of course, this is only one part of the gender gap problem in

education. Where girls fall behind in math education, more alarmingly, boys are

falling behind in all other subjects.

THE MALE DISADVANTAGE

|

| (src) |

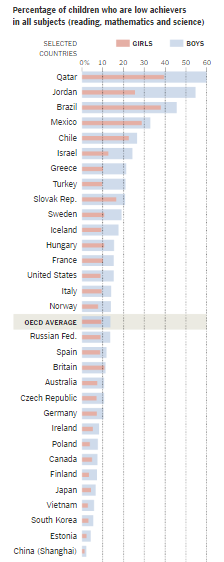

A study of academic proficiency among children of the world’s industrialized

nations shows that 60% of these nations’ underachievers are boys. And the gap

between boys and girls at the bottom is even bigger; American girls in the

bottom 94th percentile of reading tests scored 15% higher than their

male counterparts (source).

Basically, this means that the majority of underachievers are

male, and that those underachievers are truly

underachieving. But even more concerning is that in 70% of countries tested,

girls’ averages were higher than boys’ in math, reading, and science,

regardless of the degree to which the country has attained gender equality.

But why are boys now falling behind?

While there’s no way to be 100% sure about the exact reasons why,

analyzation of data allows some speculation. Because this gender gap is the widest

in poorer countries, socioeconomic development would reasonably help to narrow

the gap; in the United states, it was found that boys from single-mother homes

performed the worst, so improving the socioeconomic conditions here in America

would likely narrow the gap here.

The gap is also somewhat caused by social factors. Where girls

face math anxiety at an early age, they also face a more general challenge;

most girls, including me, are told that ‘it’s a man’s world, and you’re going

to have to work harder than them to do as well as they do.’ This might be a

generalization, but it’s likely universal. Girls have this fear-motivated drive

to do better than boys, but boys don’t.

This article suggests that boys are less motivated than girls due to schools becoming

boy-unfriendly, due to a false sense of accomplishment propagated by video

games, and due to the normalization of pornography use at young ages.

Personally, I think this problem is a larger concern than that of

the math gender gap, as it shows that boys are less motivated to do well in

school in general, whereas the math gap is only one subject area.

What do you think? Both problems should be addressed, but which do

you think is more alarming? A lot of us are Schreyer scholars; what motivated

you to do well in high school and what motivates you now?